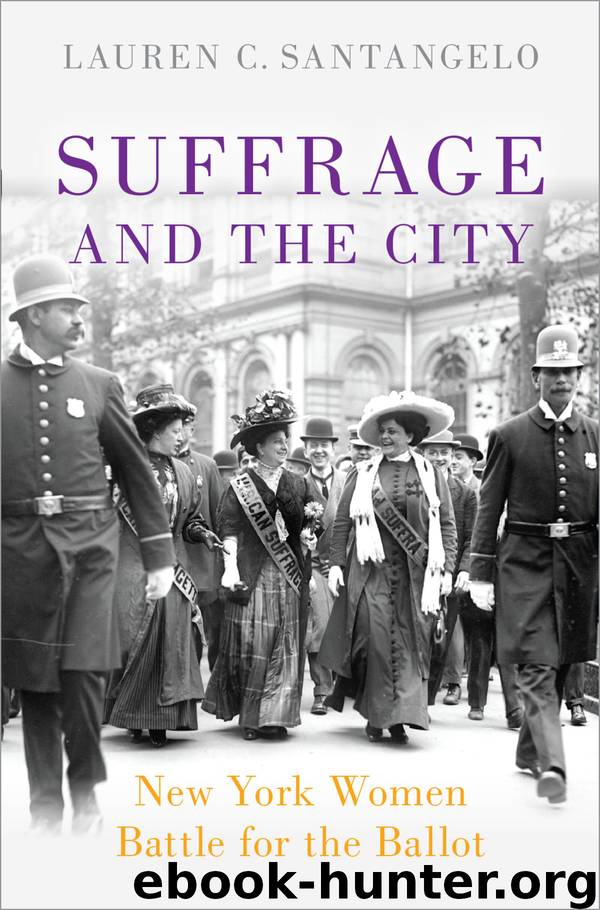

Suffrage and the City by Lauren C. Santangelo

Author:Lauren C. Santangelo

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Published: 2019-08-20T16:00:00+00:00

A cartoonist tried to capitalize on readers’ protective instincts by drawing germs threatening a toddler’s well-being and indicating that only her mother’s vote could help. Since no child was immune from the outside world, it suggested, all mothers needed the franchise in order to reform that world. The Woman Voter, May 1916, New York Public Library.

Against a backdrop where Long Islanders advocated armed resistance if philanthropists opened a polio hospital in Hempstead, some Italians in Brooklyn threatened to murder anyone who reported ailing children to the Board of Health, and everyone feared contracting the disease, this work was not for the faint of heart.59 In persevering, suffragists were performing the role of the good, informed, and active female citizen—one who supported the metropolis in its time of need and prioritized the family. They were tapping into a long history of woman’s groups, especially charities, collaborating with the government, and their work paralleled that of other contemporaneous woman’s organizations like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.60 Many activists seemed glad to capitalize on their experience to help. They had spent years canvassing neighborhoods (both rich and poor), speaking to strangers (both men and women), and tailoring arguments to reach residents (both immigrant and native-born); now they volunteered their know-how.

Civic concern alone did not motivate their generosity, however. They subtly tied their cause to the city’s welfare—at one point backhandedly bemoaning the fact that they could not devote more energy to combating the disease because they still needed to fight for the ballot.61 Organizers’ concern for the metropolis might have been genuine, but it was also savvy to link suffrage to maternalism, government aid, and disease control.

At the end of July 1916, advocates began to resume some of their routine work. The Woman Suffrage Party declared July 28 “Commuters’ Day.” Lobbyists presented New York commuters with taffy and fudge at transportation hubs like Pennsylvania Station and Grand Central Terminal.62 Along with the candies came a letter to commuters’ wives. In it, a “tenement house mother” lamented that her children “romp in the dirty and congested [city] streets; receive bad influences from low dance halls, saloons and motion picture places; suffer because of cheap food, bad air, dark and cramped quarters.” The letter provided suburban housewives, its intended audience, with a heart-rending mission: they could help these struggling mothers save their children from urban threats only by working to promote enfranchisement and thereby ensuring that all women had a voice in government. Though the message echoed previous pleas, it likely elicited a more visceral reaction as the epidemic continued to claim children’s lives.63

Suffragists transformed their political expertise into social welfare skills with the polio outbreak. Rather than confronting men in the financial district or public officials like the police, they allied with the government to eradicate the epidemic. The emergency bred opportunity for partnership, and activists capitalized on it to remind residents what enfranchising women would mean for the metropolis. Only with the vote, one journalist preached to New Yorkers at the height of the scare, could women “more effectively serve in bettering civic conditions.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1705)

The Bomber Mafia by Malcolm Gladwell(1622)

Facing the Mountain by Daniel James Brown(1553)

Submerged Prehistory by Benjamin Jonathan; & Clive Bonsall & Catriona Pickard & Anders Fischer(1455)

Wandering in Strange Lands by Morgan Jerkins(1426)

Tip Top by Bill James(1414)

Driving While Brown: Sheriff Joe Arpaio Versus the Latino Resistance by Terry Greene Sterling & Jude Joffe-Block(1374)

Red Roulette : An Insider's Story of Wealth, Power, Corruption, and Vengeance in Today's China (9781982156176) by Shum Desmond(1359)

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History by Kurt Andersen(1352)

The Way of Fire and Ice: The Living Tradition of Norse Paganism by Ryan Smith(1336)

American Kompromat by Craig Unger(1315)

F*cking History by The Captain(1302)

It Was All a Lie by Stuart Stevens;(1299)

American Dreams by Unknown(1285)

Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men who Stole the World by Nicholas Shaxson(1272)

Evil Geniuses by Kurt Andersen(1257)

White House Inc. by Dan Alexander(1211)

The First Conspiracy by Brad Meltzer & Josh Mensch(1173)

The Fifteen Biggest Lies about the Economy: And Everything Else the Right Doesn't Want You to Know about Taxes, Jobs, and Corporate America by Joshua Holland(1125)